Sam cook

The singing chef. What a turkey. Thanks to Brother Jerome for this.

Serge Chaloff “Blue Serge” on Capitol (1956) with Sonny Clark, piano; Joe Jones (Philly Joe), drums; and Leroy Vinnegar, bass. Titles include “How About You?”, “Handful Of Stars”, “The Goof & I”, “Susie’s Blues”, and “All The Things You Are”. This is a classic record and a must for any serious jazz collection. His previous date as a leader is “Boston Blow-up” (1955) and that too is essential.

Baritone saxophone player Serge Chaloff was mostly known as one of the original Four Brothers (with Getz, Steward/Cohn, and Zoot Sims) in the Woody Herman big band. Chaloff’s father was a concert pianist and his mother was a piano teacher to young prodigies like Herbie Hancock, Keith Jarrett, Chick Corea, even George Shearing. Serge, like many of his contemporaries in the jazz world, wound up with terrible addictions to booze and heroin. Tragically he died at 33 in 1957. “Blue Serge,” a tour-de-force, unrehearsed, “blowing session” was made just weeks before his partial paralysis due to spinal cancer. I read that Serge intentionally toned down the studio lights during the sessions to give an intimate, atmospheric setting and he really swings his big horn with the support of this hip West Coast rhythm section.

Jesse “Tex” Powell (Baritone Sax) “Blow Man Blow” Jubilee Records. Powell had an amazing career from the little research I’ve done. Like his more famous contemporary, saxophonist King Curtis, he straddled the worlds of Jazz (he played with Coltrane in the Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra and again in the Johnny Hodges Orchestra in the late forties/early fifties); R&B (he recorded as the Jesse Powell Orchestra with Bill Doggett before becoming the music director and house band leader at Jubilee/Josie Records and was an original member of the Cadillacs); Pop (he played with King Curtis behind some Bobby Darin hits); and Blues (he recorded with Champion Jack Dupree).

Hear about Sheila, the town’s most outstanding school teacher who secretly likes to “goof off at muff-diving shindigs”!! And many more “sexciting” stag stories.

Miles Davis All-Stars “Walkin” with Jay Jay Johnson (Trombone), Lucky Thompson (Tenor), David Schildkraut (Alto) Horace Silver (Piano), Percy Heath (Bass) and Kenny “Klook” Clarke (Drums). Prestige Records. Cover design by Hannah. The Miles Davis Quintet digs into this Richard Carpenter classic on November 7, 1967 at the Stadthalle, Karlsruhe, Germany. (This clip features Tony Williams, Wayne Shorter, Ron Carter and Herbie Hancock.)

Session 9 (April 29, 1954)

This all-star session is among the key recordings in the history of modern jazz and the saga of Miles Davis.

Paradoxically (and the history of jazz is full of such paradoxes), the prognosis for history being made was anything but good. As Jules Colomby recalled, the musicians were to meet at Birdland in the afternoon for the ride to Van Gelder’s New Jersey studio. Lucky Thompson, coming in from Philadelphia, was so late that J.J. Johnson had just about talked the others into leaving without him when the tenorist arrived. At the studio, when all was ready, Miles told Bob Weinstock that he hadn’t brought his horn. Weinstock blanched. Colomby happened to have an old, leaky trumpet in the trunk of his car and Miles was able to coax from it the great playing heard here. (He also kept the horn, with the donor’s blessings.)

“Blue ‘n’ Boogie,” the Gillespie blues classic, is treated to an up-tempo ride. This date was one of the first real studio “jams,” with space for everyone to stretch out, and Miles, J.J., Lucky and Horace average nine choruses apiece. Dizzy’s original riff gives Thompson his send-off and there are nice background touches behind the soloists throughout. The rhythm section works flawlessly. Miles returns for two choruses, and Klook has his say with the ensemble.

“Walkin'” (also a blues, based on a piece known as “Gravy” when Gene Ammons first recorded it in 1950) is the masterpiece, however. At a more relaxed tempo the soloists preach brilliant sermons; Thompson may never have played better. As for Miles, he sums up why 1954 was a banner year for him. Not so incidentally, “Walkin'” became a cornerstone of the hard bop movement.

Session 8 (April 3, 1954)This marks the beginning of the Davis romance with the mute. He employs one throughout, although it is a cup mute rather than the Harmon that would soon become his trademark on ballads, especially on the melody statements. No trumpeter has put the mute-mike combination to better use. (It was Duke Ellington, whom Miles adored, who first discovered that the microphone could be an added tone color–on “Mood Indigo,” in a recording studio in 1930.) The cup mute has a rounder, less penetrating and less biting sound than the Harmon–a different color.

The new and potent rhythm trio of Horace Silver, Percy Heath and Kenny Clarke was unveiled here. Also on hand was little Davey Schildkraut, a fine altoist in a Parker mold. (He was once mistaken for Parker by no less an expert than Charles Mingus, in a Blindfold Test, on a record from this date–“I’ll Remember April.”) He had worked with Kenton, Buddy Rich, and George Handy among others, but was already holding day jobs to support his family, and dropped out of musical sight in the early Sixties. His presence here assures him a place in jazz history, but you can’t eat that . . .

“Solar,” a most attractive Davis line on “How High the Moon” changes, is sped by Clarke’s fine brush work. Miles solos first, crisply, then alto and piano, then Miles returns for the landing. “You Don’t Know What Love Is,” an Eckstine feature in the Earl Hines book, can become mighty doleful in the wrong hands, but Miles here reminds us of Gil Evans’ remark: “Underneath his lyricism, Miles swings.” This is a trumpet feature, after the effective bass-piano introduction.

“Love Me Or Leave Me” is taken at a brisk clip, Miles transforming the melody even as he states it. Silver’s piano turn is framed by ensemble touches, and then Miles launches a driving solo, urged on by Silver’s jabs and Clarke’s brushfire. Schildkraut is inventive and swings, with a rounder, softer tone than Bird but much fluency in the ornithological idiom. Silver returns, with that unique propulsion and some Bud Powell quotes; Miles trades fours with Klook for two swift rounds and takes two more of his own before the ensemble ending, bridge by Percy Heath. Joyful stuff.

This was no slapdash blowing date, but a session more cohesive than most organized groups could manage. And it is certainly worthy of notice that this was the first Miles Davis session (and quiet possibly the very first Prestige session) recorded by the remarkable, optometrist-turned-engineer, Rudy Van Gelder, who presided over the controls at virtually all Prestige, Savoy, and Blue Note dates for may years and must be considered the definitive bebop recording engineer.

-DAN MORGENSTERN, liner notes, Miles Davis Chronicle: The Complete Prestige Recordings 1951-56.

Shelly Manne & His Men Play PETER GUNN. Music by Henry Mancini from the TV program starring Craig Stevens. Contemporary Records. Shelly Manne (drums); Victor Feldman, Conte Candoli, Herb Geller, Russ Freeman, Monty Budwig. Recorded in January 1959. Manne and his West Coast jazz band interpret a selection of Henry Mancini-composed themes from the popular late-1950s TV show PETER GUNN, including the title track and a variety of atmospheric interludes. Cuts include “A Profound Gass” and “Sorta Blue,” “Soft Sounds” and the shimmering “The Brothers”.

For the most part, television music was a vast jazz wasteland before the Peter Gunn series debuted in the fall of 1958. The show’s score made a name for composer Henry Mancini and changed the sound of televised drama. It was inevitable that Shelly Manne, Hollywood studio mainstay and a proven champion at jazz interpretations of Broadway shows (e.g., “My Fair Lady” also on Contemporary), would give Mancini’s music a more expansive blowing treatment, and the resulting album reminds us that there was more to Peter Gunn than its dramatic theme and the classic ballad “Dreamsville.” Fans of Manne’s Men should note that the album was taped during the brief tenure of alto saxophonist Herb Geller, and that it makes winning use of the vibes and marimba of added starter Victor Feldman.

“Hip Cake Walk” Don Patterson (Organ) with Booker Ervin (Tenor Sax). Prestige Records. (1964) Funky organ jazz originals by Patterson including the title cut, “Sister Ruth” and”Donald Duck.” Also covers of Earl Hine’s “Rosetta” and the Drifters’ “Under the Boardwalk.” Alto saxophonist Leonard Houston and drummer Billy James join the romp. The cover features a hip, young sister skippin’ round the Flat Iron Building in NYC.

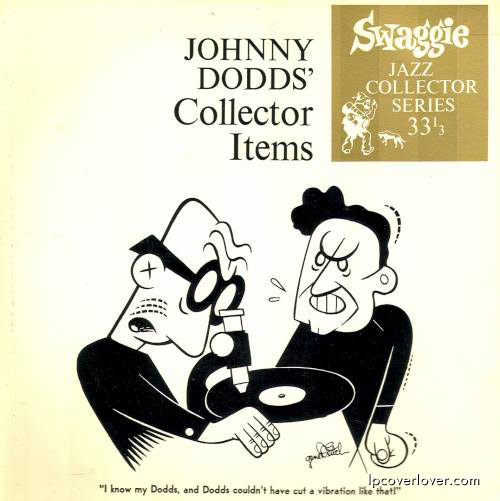

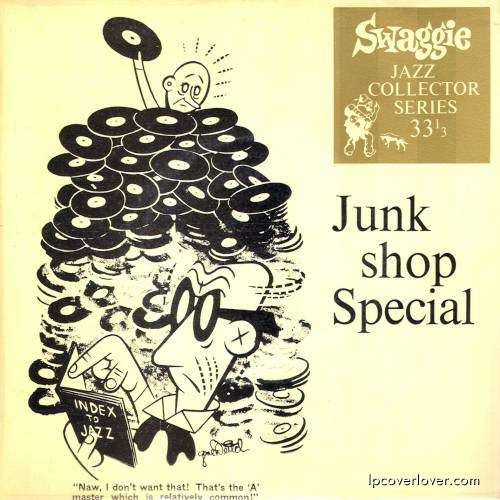

Cover art by llustrator, animator and graphic artist Gene Deitch. Two singles from Australia of Dixieland jazz from the 1920’s. On the Swaggie label. Johnny Dodds, King Oliver, etc. Among many accomplishments, including an Oscar for Best Animated Film, Deitch, in the 1940’s and 50’s, was a frequent contributor to Record Changer magazine, a magazine for jazz record collectors.