Mad men of jazz

Compendium of Jazz #1 Verve Records (1957) A compilation of Verve jazz artists including Count Basie, Stan Getz, Charlie Parker and others. (This guy is Freddy Morgan!)

Your search for charlie parker returned the following results.

Compendium of Jazz #1 Verve Records (1957) A compilation of Verve jazz artists including Count Basie, Stan Getz, Charlie Parker and others. (This guy is Freddy Morgan!)

Red Rodney A nice Prestige 10″ Features Jim Ford, Phil Raphael, Phil Leshin, and Phil Brown. Tracks: The Baron, This Time the Dream’s On Me, Mark, If You Are But a Dream, Red Wig, Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, Coogan’s Bluff

Robert Chudnick (Red Rodney), trumpeter and bandleader: born Philadelphia 27 September 1927; died Boynton Beach, Florida 27 May 1994.

AS THE FIRST white Bebop trumpet player, Red Rodney had one of the most prized jobs in jazz, playing trumpet in the quintet of the altoist Charlie Parker.

In 1945, when Rodney was 17, he was befriended by another trumpeter, Dizzy Gillespie, who in turn introduced him to Charlie Parker and the black musicians of New York.

‘I heard Charlie Parker and that was it’, said Rodney, ‘That was what I wanted to do with the rest of my life.’ He became one of the first generation of Bebop trumpet players. The others were Gillespie, Miles Davis, Fats Navarro and Kenny Dorham – Rodney survived them all.

In 1950 Parker was offered a very lucrative tour of the southern states by his agent Billy Shaw.

‘You gotta get rid of that redheaded trumpet player. We can’t have a white guy in a black band down south,’ Shaw told Parker.

‘I ain’t gonna get rid of him. He’s my man. Ain’t you ever heard of an albino? Red’s an albino,’ claimed Parker.

Rodney knew nothing of this until the quintet arrived for the first job of the tour at Spiro’s Beach in Maryland, where he was surprised to find a poster reading ‘The King of Bebop, Charlie Parker and His Orchestra featuring Albino Red, Blues Singer’.

‘You gotta sing the blues, Chood baby,’ said Parker (‘Chood’ was his nickname for Rodney, derived from the trumpeter’s real name, Chudnick).

When Parker died in 1955, Rodney joined Charlie Ventura for a short time, but his life became overwhelmed by his drug addiction and he left music altogether in 1958. He drifted to Las Vegas where, as a drug addict, he became a familiar of the local vice squad. He was sentenced several times to the federal narcotics hospital at Lexington, Kentucky.

One day he saw a photograph in a newspaper of one General Arnold T. MacIntyre. ‘Hey,’ he said, ‘I look like this cat’ A scheme took shape in his mind. A friendly printer forged some credit cards for him in MacIntyre’s name and 20 cheques, each for $1,840, the average monthly salary of a major- general. Rodney dyed his hair grey and bought a major-general’s uniform. Suitably equipped, he would walk into a bank and present himself as General MacIntyre, ask to see the manager, and flash his wad of credit cards. Using these methods he managed to live a life of luxury for a year.

He gave up drugs in 1978, his wife Helene called him ‘a born- again virgin’, and his career took off again when he formed a band with his fellow trumpeter Ira Sullivan and the pianist Gary Dial. Rodney took up the fluegelhorn to great effect. Playing better than ever before, he was in demand all over the world for clubs, concert halls and festivals and in his final years some of the best musicians of the younger generation, notably the remarkable alto player Chris Potter, queued up to join his band.

Lenny Bruce – American Fantasy Records 7011. Selections recorded in 1960 during nightclub performances in San Francisco.

Liner Notes by Ralph J. Gleason:

If there is one single theme running through the New Comedy of Dissent, it is that an agonizing reappraisal of the priorities of our society is overdue. Artists are on the picket point of all social movements and the jazz men and the satirical creative comics have been the picket points in this country ofthe great social upheaval that has shaken the entire world in the decade following World War II.

Let us not confuse the jazz musicians of the interregnum between the World Wars with the jazz musician now; the attitudes and assumptions are entirely different. The jazzmen of the 30’s, no matter how iconoclastic and no matter how rebellious, accepted as a working base the stereotype his audiences wanted.

The comedians were no less bound by ritual and by rote. World War II broke this and freed the colonial peoples of the world from their concept of subservience and this has been reflected in the jazz musician and it also shook up The Establishment sufficently so that parts slintered off and a reassessment began. Today’s dissent is not based on revising the same order of things but upon a complete re-examination and a completely new approach which abandons the pose and the pretense that had become traditional.

Comedy – especially improvised, creative comedy – bears a strong resemblance to jazz. It is rooted in the same dissent, nurtured in the same rebellion and articulated in the same language in which the priorities of the Establishment have no standing at all.

There is no better example available on record of this entire attitude than Lenny Bruce’s bit on “How to Relax Your Colored Friends at Parties” on this LP.

Done before a mixed audience, the reaction is mixed. Some non-Negroes are outraged either because they think the attitude is outrageous or because they are ashamed to have the truth so bluntly put. Others are momentarily shocked but then, as they see themselves in past moments portrayed on stage they laugh embarrassedly. Others – those few who have escaped from the chains of race to some degree – fall out.

The same spectrum of reaction is followed by the Negroes in the audience. The more courageous and the freer dig it immediately and respond. Then there are those who fear it will rock the boat inhibits them.

Thus it is with Bruce’s humor in many areas. Comedians divide in their reactions. Any of them, from the bland Bob Newhart to the salty Mort Sahl who are themselves based on the same assumptions of paradox and pretense, go down the line with him. Like Charlie Parker, Bruce’s humor is the seminal influence of his generation and a decade from now its effects will be so widespread that those influenced by it may not even be aware of it.

Bruce has already opened up new areas for other comics to explore and it is a testament to the artistic density of the structure of his art that it is so rewarding line by line and concept by concept. Any Bruce show disgorges countless asides and inferences and quick bits that can be expanded (and are being expanded) by others. Bruce has opened the door to a reconsideration of everything in our society except the basic truths of love and beauty and honesty and truth itself. He is, in essence, attacking the whole of our society from the point of view of a street-wise primitive Christian preacher. In other words, he is the child who says the Emperor has no clothes.

There are several other points which are useful to keep in mind when listening to Bruce. He, like the jazz musician, gets bored with the same routines and this has led him to improvisation and leads him now away from things which have become associated with him, making his nightly shows a different experience than his records. He may very possibly do none of the bits on this album any longer. He may probably be bored with them.

The relationship between Bruce and the jazz musicians extends into something else, too. The jazz audience is the basic audience for Bruce because jazz listening postulates familiarity with the feeling of improvisation and this is essential to understanding and appreciating Lenny Bruce. He “wails” like a jazz man, “get in the groove” or whatever he may use to describe the jazz musician’s equivalent of being “on.” You throw away the openings sometimes because he’s just getting started. And when he is in the groove, wailing and on, the whole thing swings in a jazz sense.

One other point. The New Comics, Bruce in particular, establish a very personal relationship with their audience by the simple process of extending their own intimate circle to include the audience. The audience are all personal friends. “I have to read newspapers and see TV shows so I can come back and tell YOU about them,” Bruce remarks to the audience. His entire attitude is that of the gifted commentator in the personal circle telling all his friendsabout the incredible examples of life and social behaviour he has encountered in the recent past. He does not tell jokes. He does bits and he does routines, but he also tells them directly to YOU. This is both the secret of the successand the failure of this form of the comic art. But at its best, it is somethingmore vital and alive than anything except the very best in art. Some excerpts of that order are included here.

The IMMORTAL Charlie Parker. Savoy MG12001

“The Sick Humor of Lenny Bruce” Fantasy Records (1958) Thanks to Steve Talley for sending this in!

The Liner Notes: We are living in a culture of conformity, the sociologists keep telling us as they pore over statistics that indicate college students are conservative this year. That may be. But sometimes it seems as if the sociologists miss a few points such as Bob and Ray, jazz musicians and the well-honed wit that is bringing the Comedy of Dissent these nights to various clubs in the person of Lenny Bruce.Lenny Bruce is an example of something new in our society. He’s a comic right out of the jazz world. Unlike Mort Sahl, himself a razor wit flavored with a liberal dose of jazz orientation but self-confined to a political and national affairs horizon with forays into a limited social strata bounded on one side by hi-fi and on the other by the psychiatrist’s couch, Lenny Bruce ranges throughout our society. Armed with the anarchistic wit and salty speech of the jazz musician, Bruce does his satirical bits in a multitude of voices as contrasted to Sahl who is a stark, stand-up comic monologist.

Bruce’s whole orientation is that of the jazz musician and knowing this is fundamental to understanding and appreciating Bruce’s humor. Like the jazz musician’s view, Bruce’s comedy isa dissent from a world gone mad. To him nothing is sacred except the ultimate truths of love and beauty and moral goodness – all equating honesty. And like a jazz musician he expects to see these things about him in the world in a pure form. He takes people literally and what they say literally and by the use of his searing imagination and tongue of fire, he contrasts what they say with what they do. And he does this with the sardonic shoulder-shrug of the jazz man.

He is colossally irreverant – like a jazz musician. His stock in trade is to violate the taboos out loud and to say things on stage (and on this LP) which would get your nose bashed in at a party. But his outrage at society is not represented by shrill screams or loud protests. He does not pose. His is a moral outrage and has about it the air of a jazz man. It is strong stuff – like jazz, and it is akin to the point of view of Nelson Algren and Lawerence Ferlinghetti as well as to Charlie Parker and Lester Young.

Bruce improvises the way a jazz musician does. His routines on this album, for instance, are never done the same way twice but move like a soloist improvising on a framework of chords and melody. He takes a hard look at middle-class America with its Babbitts, its Lodges, and its Elmer Gantrys. He stabs the motion picture business with brutal parody and he punctures the hypocrisy in religion, politics, and other areas with an arrowtipped with poison.

Lenny Bruce is a social commentator, as is the jazz musician. It is an interesting point for speculation as to why his comedy of dissent has flourished in the jazz clubs. He terrifies other comics – the usual ones – by his material, in the same way the jazz musician terrifies the hotel bands and the mickey mouse tenor men. He is a threat. If he is real, he gives them the lie by his very existence.

For almost two decades the night clubs have wallowed in a sea of sentimentality and pious corn and bathroom jokes. That’s why Joe E. Lewis is such a relief. He is real and so is Lenny Bruce.

The jazz musician is a rebel with humor, if with a cause, and there is no more effective putdown of the political speeches, the incongruities in the news, the fetuous posing of the tent show religious carnivals than that which goes on in the conversation of the jazz musician and the humor of Lenny Bruce.

It’s ribald. Yes, and even sometimes rough. But it’s real. You have to earn the respect of the jazz musician, he doesn’t give it because he’s told to. And this attitude, a modern manifestation of the original American “show me,” is Bruce’s strength. He’s a verbal Hieronymus Bosh in whose monologue there is the same urgency as in a Charlie Parker chorus and the same sardonic vitality in his comments as in Lester Young’s reflections on a syrupy pop tune.

The jazzman may be anti-verbal, as Kenneth Rexroth says, if so, he has Lenny Bruce to speak for him with power.

– Ralph Gleason

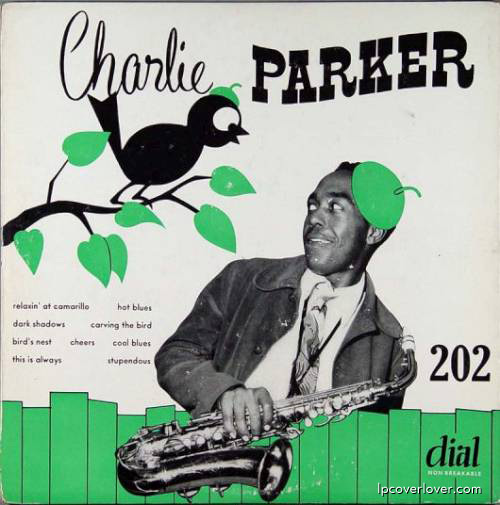

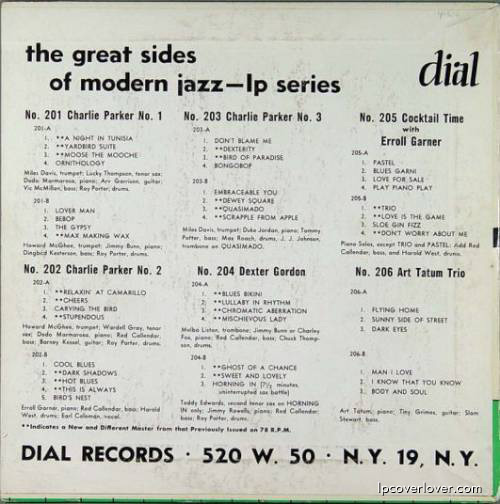

Charlie “Bird” Parker (Dial 202) From Vintage Vanguard — an amazing source of jazz album photos and information.

Three 10″ LP’s were issued in 1949- “Charlie Parker Quintet” vols 1, 2, and 3. (Dial LP’s 201, 202 and 203). Dial also released “Charlie Parker Sextet” (207) in 1950.

In New Orleans during the 1950’s and 1960’s there were many talented musicians who made a living playing and recording R&B and rock à «n’ roll. They performed on hit records by Fats Domino, Little Richard, Ray Charles, Shirley & Lee and numerous others. However, it was their hearts desire to play jazz, modern jazz, bebop. Their stories of late night jazz jam sessions are legendary. The music of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk and others made a large impact on many post World War II New Orleans musicians. There are precious few recordings of this style in New Orleans.

Compendium, by the AFO Executives, is the best recorded example of the genre. AFO, for the uninitiated, is an anacronym for All For One; it is also the name of the record label founded by Harold Battiste and his “Executives” in 1961. The name “The A.F.O. Executives” did not just happen by pulling names from a hat or secret vote or some similar arbitrary method, but is an accurate description of them because they were, are in fact, the executives of AFO Records, Inc. Having been quite successful in the studio producing record pace setters like “I Know,” the five “executives” who happened to be musicians (or five musicians who happened to be executives) began to play club dates as a group. With Tammy Lynn-the most versatile vocalist in their stable-added to the group, the stage was set for the swinginest all around group to hit the band stand.

The Executives included Harold Battiste on piano and alto sax, John Boudreaux on drums, Melvin Lastie on cornet, Peter Badie on bass, and Alvin “Red” Tyler on tenor sax. Compendium was recorded in 1963 at Cosimo’s Studio. The musicianship on this recording is exceptional and Tammy Lynn’s voice is the only known example of modern female jazz singing in the city from the 60’s that has survived. She sings, not skats, in a pure bop style. The group’s emphasis is on ensemble work instead of lengthy solos; they are tight while maintaining a loose swing. The horn arrangements and aesthetic expression make this record modern. The repertoire they chose to record reveals their Crescent City connection. There are original compositions by Melvin Lastie, Roy Montrell, Red Tyler, Harold Battiste and James Black. In addition they do very hip arrangements to tunes like Gershwin’s “The Man I Love,” Kern’s “Old Man River” and Williams’ “Mojo Hannah.” For listeners who were not around during this neglected period of New Orleans music history, Compendium offers a small glimpse into what those late night jam sessions were all about. – Jerry Brock

By late 1961, the label found great success and acclaim following the gold record success of AFO vocalist Barbara George with her national pop hit, “I Know (You Don’t Love Me No More).” The single rose all the way to number 3 on the U.S. national “pop” charts. With this financial boost, the label was then able to finance later recording projects which included the works of such young artists as Mac Rebenack (better known today as Dr. John), Willie Tee, Eddie Bo, and Nookie Boy Oliver “Who Shot the La La” Morgan. In 1963, Harold Batiste was called to California to produce the Sonny and Cher show as musical director and the label became dormant.